Another 100 acres

As we all know one of the most frustrating and difficult aspects of this hobby is obtaining permissions. It’s because of this that I feel incredibly lucky to have access to some brilliant permissions, one of which I have already written a couple of articles about at Weston in Hertfordshire. Last year around spring time it was getting close to the point where the fields at Weston would be seeded and detecting there would finish for a few months. It was on the last day of detecting that the landowner came out for a chat, and just as he was about to depart he dropped this bombshell of a line, “oh, did I mention that I have another 100 acres down the road?”.

A long wait

Wow, I couldn’t believe our luck, I say our as Weston is a permission that an old school mate and myself share together. Like Weston at this point, we wouldn’t have access to these new fields until the end of the harvest, so now we had a few months of imagining what could be out in these new fields. The time eventually came when there was a gap between harvesting and seeding so we had the chance to go out for a few days before we had proper access at the end of summer. This gave us a tantalising taste of what could potentially be lurking beneath the earth.

Between finding out about the permission and physically having the chance to get out there gave me plenty of time to do some research on the area. This brought to light some really interesting features which included a possible Roman farmstead and a large Iron Age enclosure. Having to wait a few months imagining what might be there was hard, and anyone who is as passionate about this hobby as I am will understand what I mean.

The first two days

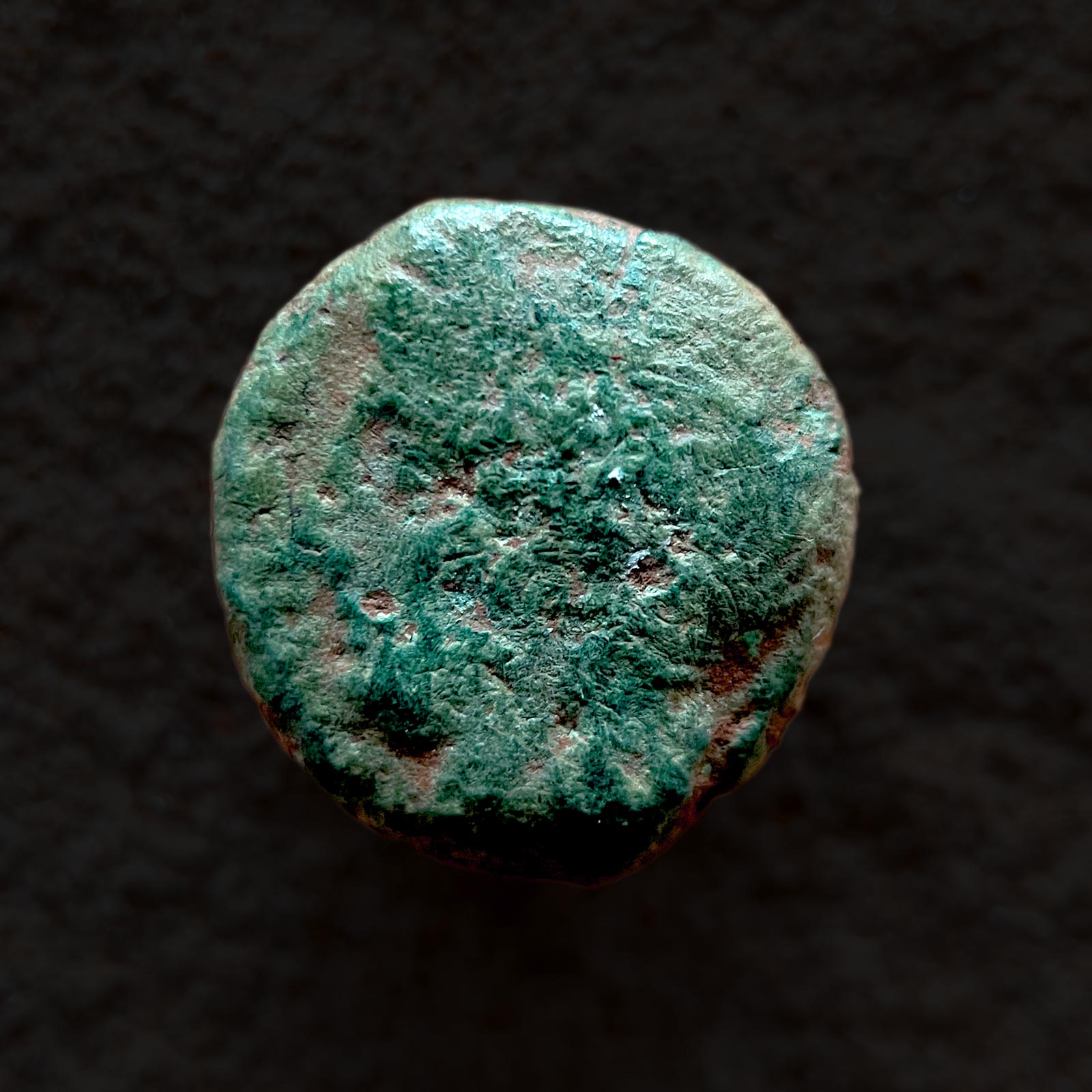

The first of two days out on this permission produced a couple of promising finds, both of them being Roman coins. The first was a very worn coin which has been described on the Portable Antiquities Scheme as follows… “A worn Roman copper-alloy dupondius of an uncertain emperor dating to the period AD 1-250. Unclear reverse depicting a standing figure, SC across fields. Mint of Rome” (Fig.1). The second coin was a big improvement and it’s the third silver denarius that I have found on my detecting journey so far (Figs.2a & b). This coin depicts Emperor Antonius Pius (AD 138-161), and even though his nose was missing and there was a few blemishes on the reverse it was a brilliant coin to find. On a slight tangent, I think back to when I was a kid in the eighties going to the local newsagent to buy a pack of Panini football stickers. I would carefully tear the wrapper in the hope of seeing a bit of silver that would indicate a team badge (also known as a shiny, those of a certain age would get this reference). It’s a bit like that with the Roman coins when me and my mate are on the permission together. On finding a Roman coin one of us would shout “Roman”, and the other would automatically reply “Sliver?”, and usually the answer would be “Nah, grot!”, but not on this occasion, this was a shiny!

Winter is coming

After those two days it would be another month before we were back out on these fields, but at least this meant we had the whole permission over the autumn and winter months. The permission itself is effectively split in two by a small river, and when I say small, it’s now barely a stream. Many centuries ago It would have been more like a river and was probably navigable as the water table in this area would have been higher back then. This may explain why the two enclosures I could see on google earth were quite close to the river. Both enclosures were on the same side of the river and on the other side there was nothing really of note, and it was the same with the finds. Pretty much everything you see in the pictures accompanying this article were found on the side with the two enclosures. But all of the finds you see here were few and far between, it’s taken a lot of walking to find this lot, and we’re talking Lands End to John O’Groats kind of walking!

Detected before?

The fact that the finds were few and far between got me wondering if this permission had been detected on before. The landowner purchased these fields 7 years ago during which time he hasn’t given permission to detect here. Before that I have no idea of what the metal detecting history of these field are, but the fact that not a huge amount has come up here and considering the two enclosures that I mentioned makes me think I’m not the first to detect here. I subsequently found out that the route of a Roman road ran right between the two features, so surely there must have been more here than what I have found? Still, a few of the things that I have found here have been pretty special.

So many buttons

As I have just mentioned the lack of finds did make me wonder about the detecting history of these fields, and I still think I’m not the first to detect here. But there was a strange anomaly on one section of the permission which was red hot with finds, a hot spot if you will. Buttons, bloody buttons, buttons, buttons, they were just everywhere in this part of the field. As you can see in Fig.3, this day was a button day and most of them were military buttons, and even now if I go to that part of the permission I can guarantee a button will come up. This does make me think that if other detectorists had been here, then surely they would have hoovered up all of these buttons? The presence of these buttons are probably the result of old World War military uniforms being dumped and ploughed into the land, something that did use to happen, much like the farmers plough in green waste today (which is a big problem to be discussed in another article). Still, all these buttons did give me hope that there would be sections of this permission that would have been missed if other detectorists had been here.

Silver and gold

As well as the denarius I found, a few other silver coins have shown their faces here too. These include sixpences, shillings and a splattering of hammered coins which can be seen with a myriad of other finds in Figs.4-8. I also found my first Elizabeth I hammered coin, a sixpence which can be seen in Fig.9a & b. But most importantly this permission is where I found my first gold. I have no doubt you will agree that this is a pivotal moment for every detectorist, being able to dance that fabled dance is a magical thing to be sure! This find came in the form of a gypsy ring (Figs.10-12) which was 18ct gold set with two rubies and a diamond. From the hallmarks I was able to decipher that the ring was made in Birmingham in the year 1897. It wasn’t particularly valuable as the ring itself had sustained some damage, but it was definitely a moment that I will never forget, a detecting right of passage ticked off the list.

Things of significance

A few other bucket listers came from this permission the first being a medieval horse harness pendant (Fig.13), something I had been wanting to find for quite a while. The pendant was quite beaten by the sands of time but it wasn’t broken. The face of the pendant is decorated with rampant lion facing left with a forked tail in raised relief and a small amount of red enamel on the outline survives. The second bucket lister was a silver Commonwealth halfgroat (Fig14a & b). These coins were minted in the period 1649-60 when there was no monarch as Charles I had been beheaded and Oliver Cromwell took power, which is why these coins were produced without a royal bust. Commonwealth coins from this period are not common finds and this little chap was just lying on the surface sunbathing.

It’s not often that you find lead items in good condition so I was quite surprised when a couple of lead seal matrix’s came out of the ground (Figs.15 & 16). Both are medieval and have been dated to the period 1200-1400. These two were found quite close to the rivers edge near to where the Roman road must have had a bridge or ford of some sort so people could cross over. I wonder if these items belonged to travellers who stopped at the riverside for a break and a drink and then lost them before carrying on their journey. Again it’s something we can only speculate at, but these lost items always make me wonder how they came to be lost, and more important how much they were missed.

Another significant find was a section of Roman Armilla bracelet (Figs.17-19), which despite being broken was in really good condition. I almost through this in my scrap pocket until I wiped away the earth and saw the decoration. I showed this section of bracelet to the now retired archaeologist Gilbert Burleigh, who was the subject of my last article.

Gil responded with the following “James, that is extremely significant. They are associated with the Roman military in the 1st century AD. They are also associated with religious sites. I’ll send you what I wrote about armilla in my PhD text”.

The following is the extract from Gil’s PHD text. “On the other hand, traces of an enigmatic military presence have been found in the form of a small-number of military dress fittings, especially in the vicinity of the ritually-used doline on BAL-1 (cf. the military finds from the ritual ceremonial hollow at Ashwell End; Jackson and Burleigh 2018, 214 & 285-90, figs. 332-5). One of the military finds from Ashwell End was a distinctive type of bracelet. This distinctive type of wide strip penannular bracelet with transverse decorative panels at the terminals has been convincingly identified as a male accoutrement, a type of military armilla awarded to soldiers in the early stages of the Roman Conquest of Britain (Crummy 2005). Distributed in the south and especially the east of England there are particular concentrations in Essex and Hertfordshire and, significantly, examples from the Harlow temple site, the Hockwold cum Wilton sanctuary sites at Leylands Farm and Sawbench (ibid., fig. 2, tables 1–2, cat. nos 11, 29 & 30), and from the religious site at Springhead, Kent (Schuster 2011, 235–6, fig. 100, nos 145–6). But the closest parallels to the Ashwell bracelet are two examples from Stead’s Baldock excavations (one from Site A, pit 405, near the Wynn Close shrine enclosure), with exactly the same décor on hoop and terminal, one of which was found in a context dated AD 50–70. The other was found on the Telephone Exchange site in 1969, not far from the Romano-Celtic temple on Baker’s Close, the other side of Clothall Road (Stead and Rigby 1986, 126, fig 52, nos. 164 & 166; Crummy 2005, nos. 16 & 18; Jackson and Burleigh 2018, 288, fig. 336, cat. 6.33, 6.34 & 289, fig. 337, cat. 6.33, 6.34, 1st-century AD). “

The permission where I found this segment of bracelet is not too far from Baldock and Ashwell, so it fits with the suggested concentrations found in Hertfordshire. I unearthed this find a few hundred meters from the suspected Roman farmstead. Could this bracelet have belonged to a retired Roman soldier living out the remainder of his days at the side of the Roman road that ran past this enclosure? I guess we will never know, but it’s wonderful to imagine the people that these sometimes once prized possessions belonged too.

A Southern Gaulish rarity

The most significant find to come from this permission is a coin that inspired the first coins minted in Britain, and it made its way to these shores from Southern Gaul (Figs.20a & b). This coin has now been registered on the Portable Antiquities Scheme, so I think it’s best to leave this with the description provided by Matt Fittock my Finds Liaison Officer.

“A Southern Gaulish copper-alloy (bronze) unit struck on a cast flan from the Gallic city-state of Massalia (Marseilles), probably dating to the late-3rd or early-2nd centuries BC, c.250-150 BC. Obverse: Laureate head of Apollo left, surrounded by beaded line. Reverse: A bull butting right, standing on exergual line, the legend MA above. ABC p. 32, no. 115.”

“This appears to be a Gaulish import of Massaliot type rather than the later British ‘Thurrock’ or Kentish cast potins that derive from the Gaulish types (e.g. ABC no. 120). Similar examples have been recorded in Britain and through the PAS (e.g. BH-96C0C1, ESS-5BFC67, BERK-838D00) and likely date to the later-3rd or early-2nd centuries BC, probably from the earliest phases of copies of Massalia’s bronze coinage in Gaul or genuine late issues of Massalia herself. This is a find of note and has been designated: For inclusion in British Numismatic Journal ‘Coin Register’.”

It turns out that this is an incredibly rare find in the UK with only 10 finds appearing on the PAS database (at the time of writing this article) when you search with the term “bronze Massalia unit”. It does make me wonder what a trader from Southern Gaul was doing in this field in North Hertfordshire well over 2000 years ago. The fact that I found this coin just outside the suspected Iron Age enclosure might suggest that some significant trades were taking place here? Or maybe the trader was just passing through and dropped the coin, we could guess at the possibilities of this story forever.

This is only the second time that I have had one of my finds listed as “A find of note” on the Portable Antiquities Scheme, the first being a rare late Iron Age loop and toggle fastener. I donated the toggle fastener to my local museum and I intend to do the same with this coin when I get it back. I think finds like these are better left for public view in a museum rather than collecting dust hidden away on a shelf in my house.

Slim pickings

I have been detecting around this permission, on and off, for just over a year now and the finds pouch seems to be less full every time I go. The last few outings have been very fruitless which feels disheartening given the quality and rarity of some of the finds that have come up during that time. I feel sure there will be more to find here but it might take the magic of the plough to bring these things close enough to the surface for me to find. In a strange twist, on my last visit I found next to nothing until the last half hour when I decided to detect on the side of the river where I had previously found very little. In that half hour 5 coins came up, admittedly they were all pretty toasted apart from a silver Victoria threepence which was in ok condition, so maybe it’s time to do more walking on that half of the permission, hmmm?!