The big permission

Back in 2022 I wrote an article for the September edition of Treasure Hunting Magazine titled “Where have all the finds gone?”. At the end of that article I mentioned that my time there had come to an end for that season, but I wouldn’t get to go back out on these fields for another couple of years.

Detecting on this permission began again in January 2024, and now that I had a map outlining all the fields which were part of this permission I was able to do some proper research into the area. This included using Google Earth, the Heritage England Aerial Archaeology Mapping Explorer, the Heritage England Aerial Photo Explorer, and scouring through endless aerial photos on the Cambridge Air Photos website. Having access to all these online tools gave me a brilliant insight into where would be good locations to start the detecting journey here once again. I spent my first afternoon in a field which was next to the one that contained the Roman villa which featured in the 2022 article. Not a lot came up, but on walking back to the car these two little silver gems in Fig.1 appeared. The brooch, with a thistle design, is hallmarked which tells me it was made in Chester in 1913 by Charles Horner, the button, though a bit worse for wear, is roughly dated to the 18th Century (Georgian), a nice end to an otherwise crappy afternoon.

On the romans

My second port of call was the corner of one field where a rectangular enclosure had shown up on google earth and some of the aerial photography. Fortunately for me I am now also able to ask questions of Keith Fitzpatrick-Matthews (the Curator and Heritage Access Officer at North Herts Museums) and Gilbert Burliegh (the retired archaeologist who oversaw the excavation of the Ashwell ‘Dea Senuna’ Hoard, and the once former boss of Keith). I showed the aerial photography to Gil and asked for his thoughts on what it might be which were as follows… “It looks like a Romano-British ditched enclosure, possibly originating in the late Iron Age”. It would turn out that his assumptions from looking at the aerial photography would be spot on!

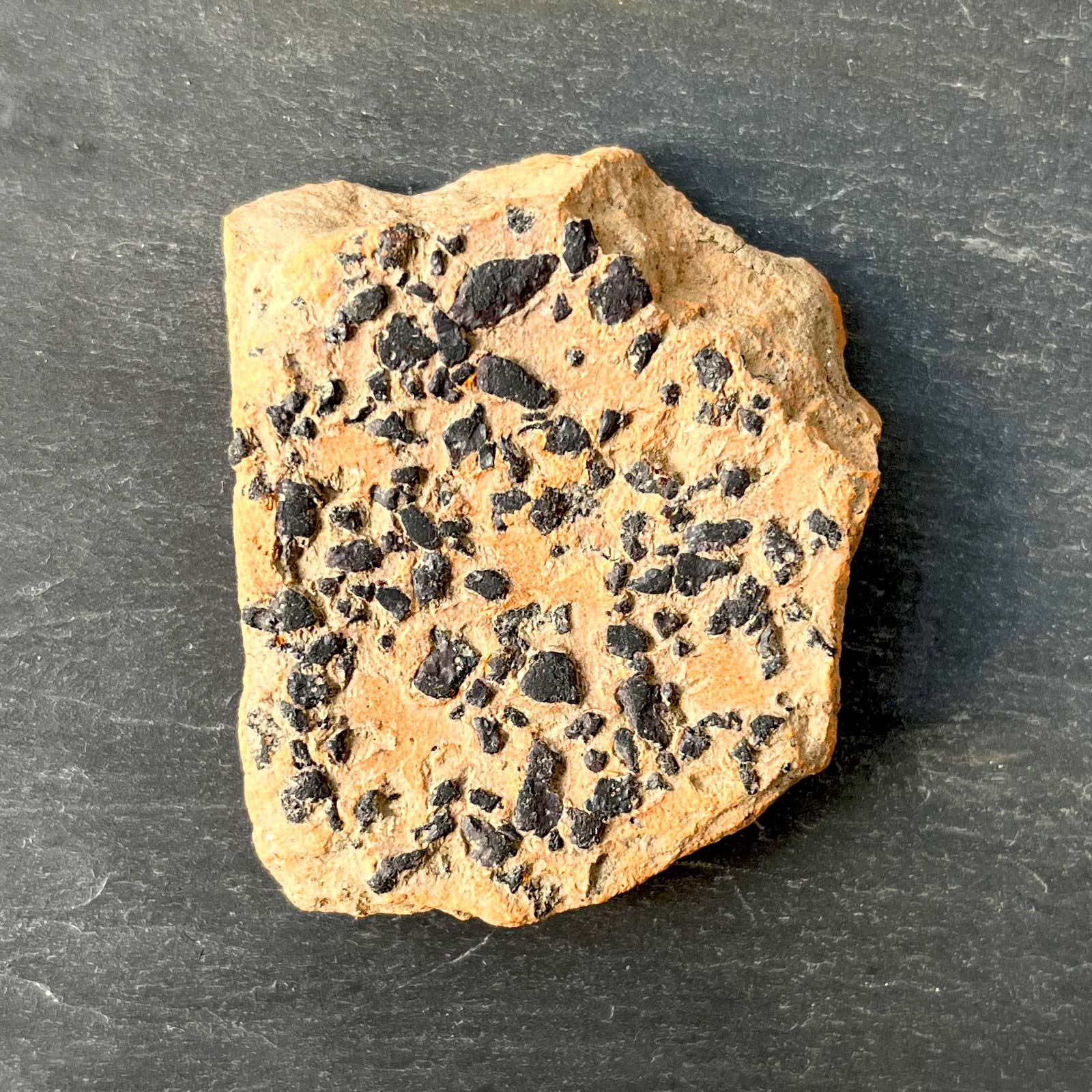

The first day on that corner of the field was cold but sunny and the green shoots of a crop had just started to push through (Fig.2). Even though this was the case it didn’t stop me from spotting pottery sherds scattered around, and lots of them (Fig.3). I messaged Keith to see if it was ok to pick some up to bring in to him to identify, which was fine as long as I provided the find spot locations as well. It turned out that most of it was Roman, but one sherd in particular was part of a mortarium (Fig.4), which in modern terms is part a mortar bowl with which we use a pestle to grind herbs and such. With all this pottery scattered about it wasn’t long before the Roman coins started to pop up. I had 12 Roman coins in all (Fig.5) and then rather pleasingly a Celtic Tasciovanos Verlamio bronze unit (20BC-10AD) turned up as well (Fig.6), which fits with Gil’s thoughts on the site perfectly, ten out of ten for Gil!

The silver denarius

Within the coins on Fig.5 you will notice that there is a silver denarius, which when I found it was a real heart stopping moment. The reason being is that the first side of the coin I saw was the reverse which carried the word Caesar (Fig.7a-7b). I can only think of one man when I see or hear the word Caesar and that is Julius Caesar. For a moment I was overwhelmed with finding a coin of one of the greatest historical figures ever known, until I sent a photo of it to Keith who immediately came back and said that it was his great nephew Octavian. But this was still impressive, to find a silver denarius from the Republic era and one which carried the head of Octavian who later became Augustus Caesar and founded the Roman Empire. This particular coin dates to the period AD 32-29 BC (RIC I 257, RSC I Augustus 61) and it is said to refer to the Battle of Naulochus. I mentioned this because the Battle of Naulochus took place on 3rd September 36BC, the date of which (excusing the year) is my birthday, how cool is that!

Towards the end of 2024 I attended a talk which Keith Fitzpatrick-Matthews gave on the history of the local area, part of which was my permission. It turns out that the silver denarius of Octavian which I had found became a small feature of his presentation and Keith has kindly shared that part of his talk here.

“The discovery of a silver denarius of Octavian is unusual from an Iron Age to Romano-British farmstead. Its reverse legend Caesar Di(vi filius), ‘son of the deified Caesar’, shows the future emperor Augustus positioning himself as the rightful ruler of the Roman world around the time of his conflict with Mark Antony and Cleopatra VII for dominance.”

“Republican and early imperial denarii do sometimes turn up in Roman contexts in Britain: more than 2000 have been found. Some were brought in by the armies of invasion or circulated as part of the general introduction of Roman coinage, but others come from pre-Roman Late Iron Age sites. Some were imported to be melted down into coins struck by British rulers, including Tincomarus and Epillus of the Atrebates, while others were used as coins because their weight matched that of British coinage”.

Not a lot else came up on the site of this enclosure, but maybe more will turn up after the plough in a few years.

Across the road

This wasn’t the only site of interest that I had spotted in my research, on the other side of the road there were more rectangular features which needed my attention. Beyond the trees (Fig.8) was a huge field that had a lot going on in it and as always I was hopeful of finding lots of Roman goodies. The field I was stood in when I took the photo of the trees also had a rectangular feature in it but as yet I have not been able to detect there as it is currently occupied by a massive badgers set (Figs.9-10).

The bigger field beyond the trees didn’t produce the Roman bounty I was hoping for, but a few interesting things from various time periods were unearthed. There were a lot of finds from more modern times here, particularly buttons and coins as seen in Fig.11, but included in this shot is a small Celtic Unit (the toasted green nugget on the top of my finger). It wouldn’t be long before a few finds of a more significant variety would show themselves.

Two of those finds which I found on the same day were part of an Anglo-Saxon brooch, and a couple of broken fragments of a Roman Armilla bracelet (Figs.12-14). The pieces of Armilla don’t feature in the group shot (Fig.12) because they were in my scrap pocket at the time. It’s only when emptying my scrap pocket that I noticed the decoration which I recognised from a piece of Armilla which I found on another permission. When I showed these items to Gil, he replied with the following… “James, that is extremely significant. Armilla are associated with the Roman military in the 1st century AD. They are also associated with religious sites. Your site is shaping up to be very interesting indeed, not least because you have early pagan A-S evidence too”.

It’s worth mentioning at this point that the association of these bracelets with the Roman military is being questioned. Keith kindly steered me towards a PhD thesis authored by Dr Edwin Wood. Keith said “Something you may not be aware of is that Dr Edwin Wood has examined the distribution of so-called armillae in Britain in his PhD thesis and has discounted their military origin”. Keith continued to say “Interestingly, he compares their decoration with the recently-classified ‘Baldock torcs’ and with a particular type of nail cleaner associated with the town. I know that the interpretation of these bracelets as military is received wisdom and that anything supposedly associated with the Roman army gets people excited, but it might be good to throw out Wood’s significant doubts to a wider public”.

Another day in this field produced a few Roman coins and a beaten up silver hammered along with the usual buttons and modernish coins (Fig.15). But in the middle of all this was a piece copper alloy (which I assumed due to the green patina), and it was something that I had not seen before. This turned out to be part of a horse harness bridal bit (Fig.16) and I have just had it confirmed by FLO that it is from the Roman period. So with all the evidence that I have found so far in this short period of time, I think it’s safe to say that this area had been inhabited by the Celts, Romans and possibly the Anglo-Saxons, the picture these finds are building is starting to get interesting. It wasn’t long before this part of the permission was out of bounds due to the crops growing, but there were other parts of the permission still available.

The finds are scarce but still coming

I now moved to another part of the permission where things were looking quite busy on google earth. It was a section where there appeared to be lots of old boundaries all crossing over each other which shows up on multiple images on the google earth historical imagery time slider. This field was available for a couple of weeks so I made the most of the time, not a lot came up here but there was still evidence of Roman occupation. I found another piece of Roman mortarium (Fig.17) along with a copper alloy Nummus of Crispus Caesar (AD 317-326) (Figs.18a-18b), so the Romans were definitely around mixing their herbs and medicines.

Some more modern items showed up too including what I believe to be a book clasp (Fig.19) which was intricately decorated with Christian symbolism which conveys hope, faith and charity. I wonder if may have been part of a bible as there is a small village church just a stones throw from this field. Another day of detecting in this field produced my first complete silver spoon (Fig.20), albeit completely bent and twisted. But even so, the hallmarks were intact which told me that this spoon dated to 1804 and was made in London by William Ely & William Fearn, I wonder if there is a spoon missing from the family silver in one of the homes in the village, I’m sure someone got in trouble for that many years ago. You will also notice in Fig.20 a Roman coin at the top of my hand which has a hole in it, I assume because it was worn, possibly as a necklace? It’s something which features on a few of the Roman coins I have found here, so it seems it may have been a popular thing to do. It wasn’t long before this part of the permission was out of bounds too, so then onto the next part!

The roman road

This time I was heading into a field which my research showed had a Roman Road running right the way through it. In fact this road ran past the big Roman villa complex which was in the first article that I wrote about this permission way back in the September 2022 edition of Treasure Hunting Magazine. I also found out that a Geophysics survey had taken place on a cross section of this field by the Community Archaeology Geophysics Group (CAGG) which showed part of the Roman road, so I knew it was definitely there (Fig.21).

As you can imagine I was quite hopeful of finding some good Roman artefacts here, but again I didn’t have a huge amount of time before this field was out of bounds too. But on the few outings that I did have there were some nice finds as you can see in Fig.22. Amongst this lot was a corroded Dupondius of Vespasian (Fig.23) along with my first Roman brooch to come up from this permission (Fig.24-25), I believe this to be a Hod Hill type brooch which would date it to the 1st Century AD. None of these things are in particularly great condition, but they are all indications of the people who were travelling and living in his area which is one of the reasons why I enjoy this hobby so much. Another little item which came out of this field was a cloth seal from the 1700’s (Fig.26-27). This one depicted the head of Queen Anne (1702-1707) and on the reverse has a rearing unicorn with the number 3, which was its subsidy value of 3p. I was quite chuffed with this little find as lead times from this period don’t usually fair so well in the ground.

Another first came up in this field which I thought was just a worn out silver sixpence (Fig.28), but curiously I noticed some stamp marks on one side. I decided to post this on a detecting Facebook page and one member came back with the following info. “Originally a William III sixpence, very late 1600’s, then later on re-used in the late 1700’s, early to mid 1800’s. They were counter marked commonly by Irish workers as they are known in the detecting world as “Irish slap tokens”. This is another great aspect of the hobby, which is people are willing to share the their knowledge, you learn something new everyday, eh.

My first treasure case

The slap token was the last find before moving onto the next part of the permission which was literally just over the hedge from this field. This was actually two fields and again I wasn’t going to have long to search them, in actual fact over two weekends I spent two afternoons on them. I will cut to the chase on this part of the permission because most of what came up was scrap pocket fodder, apart from the three lovely items in Fig.29. I’m sure most readers will recognise the broken Edward I penny and the threepence of Elizabeth I, but the third item is new one on me, is it on you?

This pretty little bouquet (Fig.30-31) turned out to be my first treasure case would you believe, and what follows is the summary of the find from the British Museum. “An incomplete Post Medieval silver gilt dress-hook dating c. AD 1500-1600. Read’s Class D, type 6. The dress-hook consists of a trefoil shaped plate with petaled edges and separate soldered transverse attachment loop. The separate soldered wire hook is missing, leaving traces of solder”.

It was pretty cool to have my first treasure case go through, but it did amaze me that this little thing constituted as treasure. I had it in my head that treasure meant vast hoards of gold and silver, not a broken dress hook. Still, a nice little find none the less which all adds to my experiences of being a detectorist.

A deserted medieval village

Now I’m finally getting closer to where I want to be, the site of a deserted medieval village. I will be honest, as much as I did want to detect on this part of the permission I wasn’t too hopeful of finding that much as the village had been extensively excavated by archaeologists the 1970’s. Since then I believe a fair few detectorists have covered the area over the years but to my surprise a few nice things came up. These included a broken part of a medieval zoomorphic vessel handle (Fig.32), a hammered Half penny of King Henry V (Fig.33), a crotal bell which was a ringer (Fig.34) and another zoomorphic end of a medieval pot handle (Fig.35). There was also plenty of general detecting pocket fodder as seen in fig.36.

Meeting new friends

It was also around this time that I met another detectorist called ‘Dal’ out in the field who also had permission on this land. Weirdly we had been following and chatting to each other on instagram for about a year or so not knowing we shared the same permission. Since then we have been out a few times together with varied results. The first time we met was at the end of one of my sessions where I had found a mass of buttons as seen in fig.37, he on the other hand had just found a Roman finger ring, not precious metal and broken but still a bloody good find.

The last time we went out it was my turn to have the find of the day. But before I get to that, I found out that during the excavations of the medieval village in the 1970’s, the archaeologists were a little puzzled that they had bits of Roman and Celtic archaeology turning up here and there. It now transpires that with the help of aerial photography it looks like there was a Roman settlement of some kind in the same field, which probably started life in the late Iron Age. Well, with the next set of finds I would say that’s a strong possibility.

The Romans and the Celts

Finally I was in the field I had been longing to get into, it hadn’t been possible before now because a crop had been in for quite sometime, but now it was coming out. Even better than that the field was being deep ploughed so hopefully new finds were being brought up to the surface! We had a morning on the field before we were told we couldn’t have anymore time as another crop was going straight in, which as you can imagine was incredibly disappointing. But the handful of stuff I did find (Fig.38) in those few hours gave me a glimpse of the history that was potentially there. In that handful of stuff was a beaten up Celtic bronze unit (Fig.39) which had just enough left on it for me to identify. This barnacle encrusted morsel is actually a bronze unit of Cunobelinus which dates 10-40 AD, so the Celts were here, now what about the Romans?

Well, on another trip out on this field we were allowed to go over one corner where the sugar beat crop had been stored. Now the crop had been moved we were free to give that little area the once over. To my surprise just lying on the surface was this belter of a Silver Denarius with the face of Hadrian just starring back at me (Fig40a-40b). The coin dates to 133-135AD, and depicted on the reverse is Salus, the Roman Goddess for wellbeing and safety. It was my eye that caught a flash of silver first but my detector confirmed the fact. But I did wonder why it was just lying on the surface and it now occurs to me that it must have come up with the beats and then fallen off as they were being moved to storage. This quite rightly suggests (I think) that this coin has come from another part of the field, but where?

Roman detail

The detail on this coin as seen in Fig.41 is pretty much in mint condition, which might mean it’s part of a larger collection of coins that were all buried here before they were used. Lol, that’s just me fantasising about finding my first hoard, but who knows, maybe this coin does have a few brothers waiting to be found. At the very least these finds go someway to confirming the origins of a possible Romano-British settlement, which is further supported by Dal finding a Roman disc brooch with some glass decoration and gilt still intact.

Time for a memoir?

It’s going to be while before we can get back into this field but it’s great to know that there is the potential for more finds to be found. It can be frustrating the amount of time us detectorists have to wait to sometimes get into certain fields, but I find it does leave time for other pursuits like writing these articles which is also a great part of the hobby for me. Maybe one day I will be able to write my detecting memoir just like Julian Evan-Hart has done, although mine would probably be better titled as ‘My Detecting Strife’.