the archaeologist ahead of his time

Somebody, somewhere said to me that a great way to obtain permissions is to politely ask the question on Facebook community pages. Specifically ones which are hosted by villages, the reasoning being that local farmers and landowners are more likely to be living in villages than big towns and cities. I liked the logic so I decided to give it a go. I put out a small post on several community groups of the local villages near me and waited for the permissions to roll in… hhmmm!

I would love to say that the permissions came in by the bucket load… sadly they didn’t, but I did get a response which led me to writing this article. I had some inquisitive and very positive comments which was really good to see, but one comment mentioned that there was a battle site close to one particular village which involved King Offa (Fig. 1). This is something I had read about in local history books so I thought it was fact, but then another member of the village replied with the following insightful post.

Fig 1. A section of the mural on the side of Hitchin library depicting King Offa, Tovi the Proud and John De Balliol, all of whom have links with Hitchin’s rich history.

“This is a local myth that arose in the 19th century after quarrying in the 1790s and 1830s uncovered the remains of a graveyard in which some of the skeletons were accompanied by weapons – swords, spears and shields. Nineteenth century antiquarians leapt to the conclusion that the burials must have been warriors killed in a battle between Anglo-Saxons and Danes – hence the subsequent name given of Dane Field (Fig. 2). More likely it is an earlier pagan Anglo-Saxon cemetery when it was not uncommon for some of the dead to be buried with their weapons, having usually died of natural causes, not in battle. Archaeological excavations on the field close to the burial ground in the 1990s revealed an early Anglo-Saxon settlement to which the cemetery probably belonged. I’m an archaeologist and resident of the village and have been working with responsible metal detectorists for nearly fifty years, if you want to get in touch.”

It goes without saying that I got in touch, and to my surprise the archaeologist in question was Gilbert Burleigh. Gil has been involved with some major archaeological discoveries in his time, some of which will be discussed and displayed within this article. But the thing that struck me, as I’m sure it has you, is the fact that Gil has been working with responsible detectorists for nearly 50 years. I was quite taken aback by his statement, an archaeologist working with detectorists since the very beginnings of the hobby in the 1970’s? I was lead to believe that during those early years archaeologists absolutely detested detectorists? There is an old saying that ‘never the twain shall meet’, and as you will see it resulted in the discovery of some amazing treasures. As a side note I think there’s inspiration here for Mackenzie Crook to write a new series, maybe Andy and Lance as kids trying out their first detectors and the 1970’s/80’s soundtrack would be brilliant. Apologies, I daydream and digress.

Fig 2. Dane Field.

After making contact and a few email communications later, Gil agreed to let me meet with him to discuss his career, the archaeological delights that he’s been involved with and more surprisingly his inclusion of metal the detecting community. Before we met, Gil was kind enough to provide me with a short autobiographical background about his career, with in which was the following insight to his views and relationships with detectorists (it’s almost like this article is writing itself).

“Over the years, some people have said to me that I’ve been very lucky in some of the spectacular discoveries I’ve been involved with and I reply that one can help make one’s own luck. For example, at North Herts Museums I began recording responsible metal detectorists finds in January 1976, in the early days of the hobby. Like the late Tony Gregory at Norfolk Museums and Kevin Leahy in Scunthorpe, independently, I continued recording their finds and working with them all through the years, including the many years from the late 1970s through to the late 1990s when the detecting and archaeology communities were, largely, vigorously opposed to each other.”

“I took the pragmatic view that the detectorists would carry on detecting regardless of what archaeologists thought, so we might as well record as many finds as possible. Most of the archaeological community finally came to this view with the launch of the Portable Antiquities Scheme (PAS) in 1997. I think that because I had good relationships with many in the local detecting community they brought their finds to me for recording between the beginning of 1976 and the end of 2003, when a PAS officer, Julian Watters, was appointed for Herts and Beds, based at the Verulamium Museum in St Albans (Fig. 3).”

Fig 3. The Verulamium Museum at St Albans.

Photo copyright St Albans Museums.

“For several years after his appointment, I assisted Julian with the recording of finds from North Hertfordshire. In return the detectorists received expert written identifications, accompanied by top-quality illustrations (Fig. 15) of their finds. Undoubtedly, because of this carefully nurtured relationship over many years some extraordinary finds were reported to me by detectorists which might not have been had the good relationship not existed.”

“Amongst these, I count the unique Pegsdon 1st-century AD Roman gold coin hoard found in 1998 (Curteis and Burleigh 2002); the Pegsdon 1st-century BC Iron Age decorated copper-alloy mirror and accompanying silver bow-brooch found in 2000, from a cremation burial, one of the earliest and most complete in the contemporary mirror series (Burleigh and Megaw 2007); and the Ashwell 4th-century AD Roman gold and silver temple treasure hoard found in 2002, only the third such hoard found in Britain and the first since the 18th-century (Jackson and Burleigh 2018).”

meeting gil

It was a weekday afternoon when I met Gil who had very kindly invited me to his home. He greeted me with a warm smile and very welcoming handshake, then showed me into his living room where we both sat down and discussed all things relating to archaeology and metal detecting. Almost immediately it was very apparent that Gil was genuinely interested in me, why I got into detecting and the coins and artefacts that I had found on my detecting journey so far. There was no sense of snobbery, animosity or distrust from him which a lot of people seem to view as the archaeologists standard stance on detectorists. In fact it was quite the opposite and it’s the same warm and welcoming view I’ve had from My Finds Liason Officer Matt Fittock and from Keith Fitzpatrick-Matthews the Curator and Heritage Access-Officer at North Herts Museums. Both Matt and Keith have been very patient and accommodating in the time that I have known them and they have also contributed to some of my past articles which have featured in Treasure Hunting Magazine.

Chatting with Gil went at a very leisurely pace and it was great to get more insight from him about the wonderful discoveries he has been involved with which he puts down to his long lasting relationships with detectorists. Gil has also very kindly provided a lot of the imagery for this article from the sites’ archives, so there is plenty for all of us to ogle at. But the best thing is that all of these wonderful treasures were found by detectorists, which gives me hope that one day you or I could be the finders of such amazing artefacts. Before we met, Gil provided me with his CV to read which included more detailed information about each of these discoveries, so I have included some extracts from those as well as Gil’s personal insights he discussed with me. Hmmm, this article is back to writing itself again.

Fig 4. Pegsdon 1st cent. AD hoard of gold aureii. Enq. 2304.

Photo © The Trustees of the British Museum.

pegsdon gold coin hoard

“Shillington A & B, Bedfordshire: 127 aurei to AD 78, 18 denarii to AD 128”, in Richard Abdy, Ian Leins & Jonathan Williams (eds.), Coin Hoards from Roman Britain Volume XI, with Mark Curteis, 2002, Royal Numismatic Society Report on the discovery by metal detectorists in 1998 of an early Roman hoard of gold coins and its significance.

The Pegsdon Gold coin hoard (Figs. 4, 5 & 6) is a discovery that I personally remember as it was often talked about down the pub at the time. This was way before I got into detecting but it was one of those things that became a bit of local legend as there was speculation about the amount of money that the detectorists received for finding the hoard. When I asked Gil about his memory of it I stayed away from the monetary side of things and he recounted the following.

Fig 5. Gold Roman coin Pegsdon – gold aureus of Vespasian rev. & obv.

Photo © The Trustees of the British Museum.

Fig 6. Gold Roman coin Pegsdon – gold aureus of Nero rev. & obv.

Photo © The Trustees of the British Museum.

“The hoard was found in 1998 and that is an interesting story. The two detectorists who found the hoard, who were on the land with the permission of the land owner, discovered it just a stones throw from the main farm house. They had been reporting things to me off and on for a few years up until that point, but this particular day was a day off of mine and they called me on my home phone and said, “Gil, we have something that you might like to see”.

“A couple of hours later the two detectorists turned up at the house with a brief case and proceeded to tip the contents of it onto the kitchen table. There was something like 112-113 gold Roman coins in mint condition that were staring back at me. The detectorists told me they had all been found in a relatively compact area, so I said we have to go back because there’s going to be more!”

“So myself and the two detectorists went back to the site and we started searching outwards from the find spot. We found another 16 gold Roman coins, so that made it 127 gold aureii in total. We found these along with some other silver denarii, I suspect they were from a separate hoard which were later in date, second century I believe and there were around 17 or 18 of those.”

Fig 7. Pegsdon copper-alloy Colchester brooch. Enq.1887.

Photo by Jane Read, North Herts Museums.

Fig 8. Pegsdon enamelled copper-alloy

crested owl plate-brooch. The owl was a companion of Minerva who was equated

with Senuna. Enq.2308. Photo by Jane Read, North Herts Museums.

Fig 9. Pegsdon Romano-British copper-alloy lyre-shaped mount. The disks on the top and bottom of the mount may represent the sun and/or moon. Enq.1887. Photo by Jane Read, North Herts Museums.

Fig 10. Pegsdon copper-alloy coin of Cunobelin rev. & obv. Enq.2304.

Photo by Jane Read, North Herts Museums.

Hearing Gil recount his memory of the gold Roman coins made me think how amazing it would be to find even one such coin, but 127 that are in mint condition, that really is the stuff that dreams are made of! Gil also provided some images of other finds that have been made around the same area (Figs. 7, 8, 9 & 10) which are also amazing artefacts in their own right.

pegsdon iron age mirror

“The Iron Age mirror burial at Pegsdon, Shillington, Bedfordshire: an interim account” With Vincent Megaw in the Antiquaries Journal, vol. 87, 2007, pp.109–40; Society of Antiquaries of London

Abstract: In November 2000 metal detectorists located a decorated copper-alloy mirror, a single silver Knotenfibel brooch and some pottery sherds at Pegsdon, Shillington, Bedfordshire. Subsequent excavation of the findspot uncovered a Late Iron Age cremation burial pit associated with further pot sherds and a single fragment of calcined bone. The opportunity is taken in this preliminary account to revisit both the occurrence in southern England of the brooch type and to discuss the mirror’s decoration in relation to the variation of views as to the British mirror series as a whole, and in particular with regard to other recent mirror discoveries. The burial is discussed in its local context and the possible significance of the topography in relation to the site is highlighted.

Fig 11. Pegsdon Iron Age mirror decorated back. Photo © The Trustees of the British Museum.

It amazes me that the things we unearth are sometimes in superb condition, especially with the amount of time they have spent in the ground. In the case of the Pegsdon Iron Age Mirror (Figs. 11 & 12) that’s over two thousand years. But it also amazes me that these things often shed light on the fact that day to day life 2000 years ago was not all that different to how it is today. Even back then taking pride in your appearance was made all the easier with the use of a mirror, although I do believe they had a lot more significance and meaning than they do today. Gil reflected (see what I did there, lol) the following about this wonderful find…

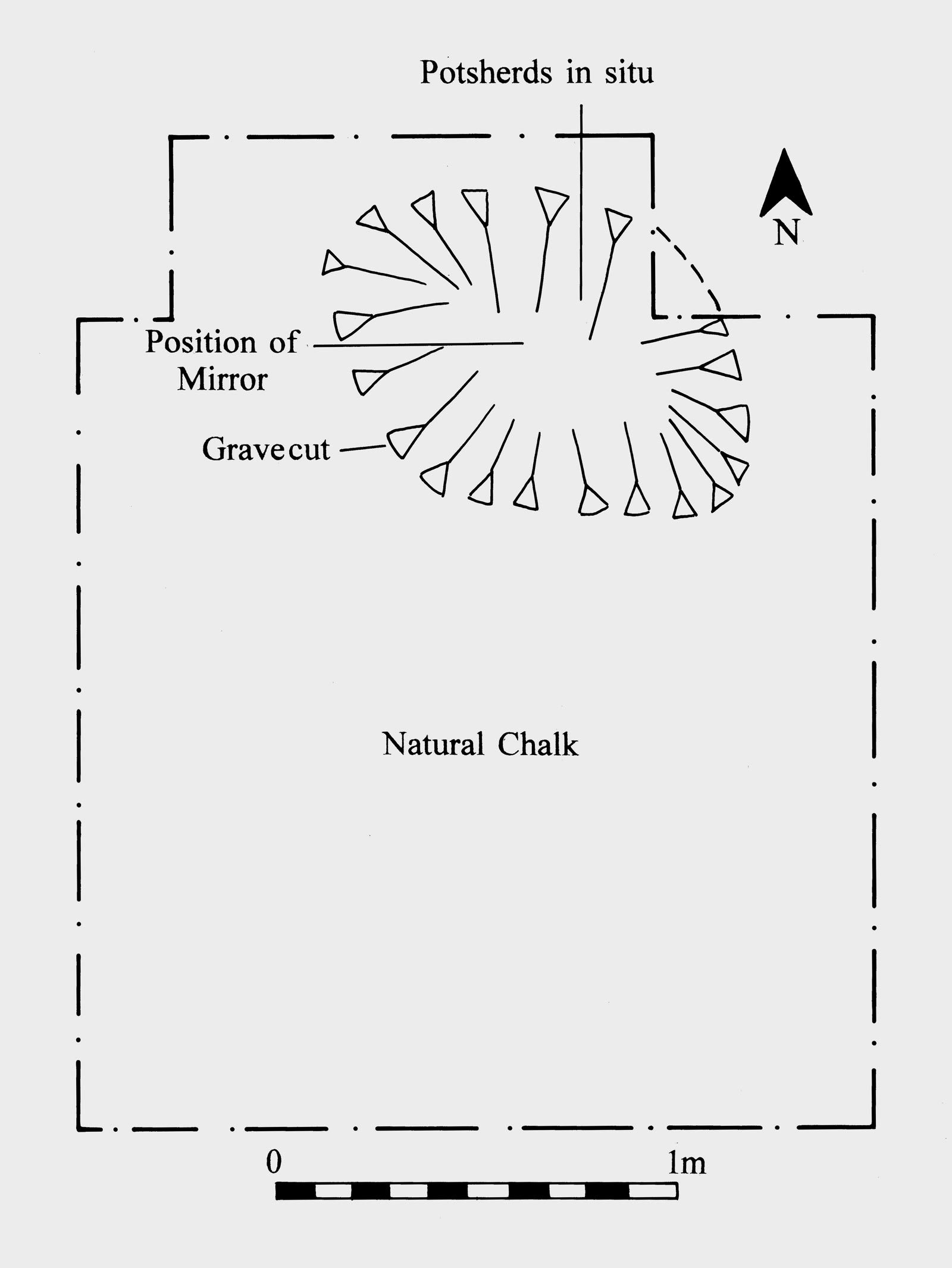

“A few years later the same detectorists who had found the Roman gold coin hoard found a late Iron Age decorated bronze mirror accompanied with some broken pot fragments along with a silver brooch which was also late Iron Age (Fig. 13). This time we couldn’t go back to do further investigation at the find spot until a year later because of crops being sown and the farmer didn’t want us poking about (incidentally this was the same field that the Roman gold coins were found in). So when we did go back to carry out a small excavation, just the two detectorists and me, I was able to define a grave pit”.

“There had been a cremation burial in a pot with a pedestal base, a very distinctive late Iron Age urn type, accompanied by a flat-based jar, and we found some more fragments of the urn along with some cremated bone. With that I was able to work out where everything was positioned in the grave pit (Fig. 14), it’s incredibly useful to be able to put the discovery in its archaeological context, which as an archaeologist is the main thing you want to achieve, so that was brilliant”.

“Of course, Iron Age mirrors, rarely found artefacts, were of much greater significance than simply for personal grooming, with their implied attributes of power and of the magic associated with the imagery of light and reflection, fire-making, and capability to dazzle, they were used in religious ceremonies to impress, usually by priestesses; for when associated with burials the identified human remains are almost all female”.

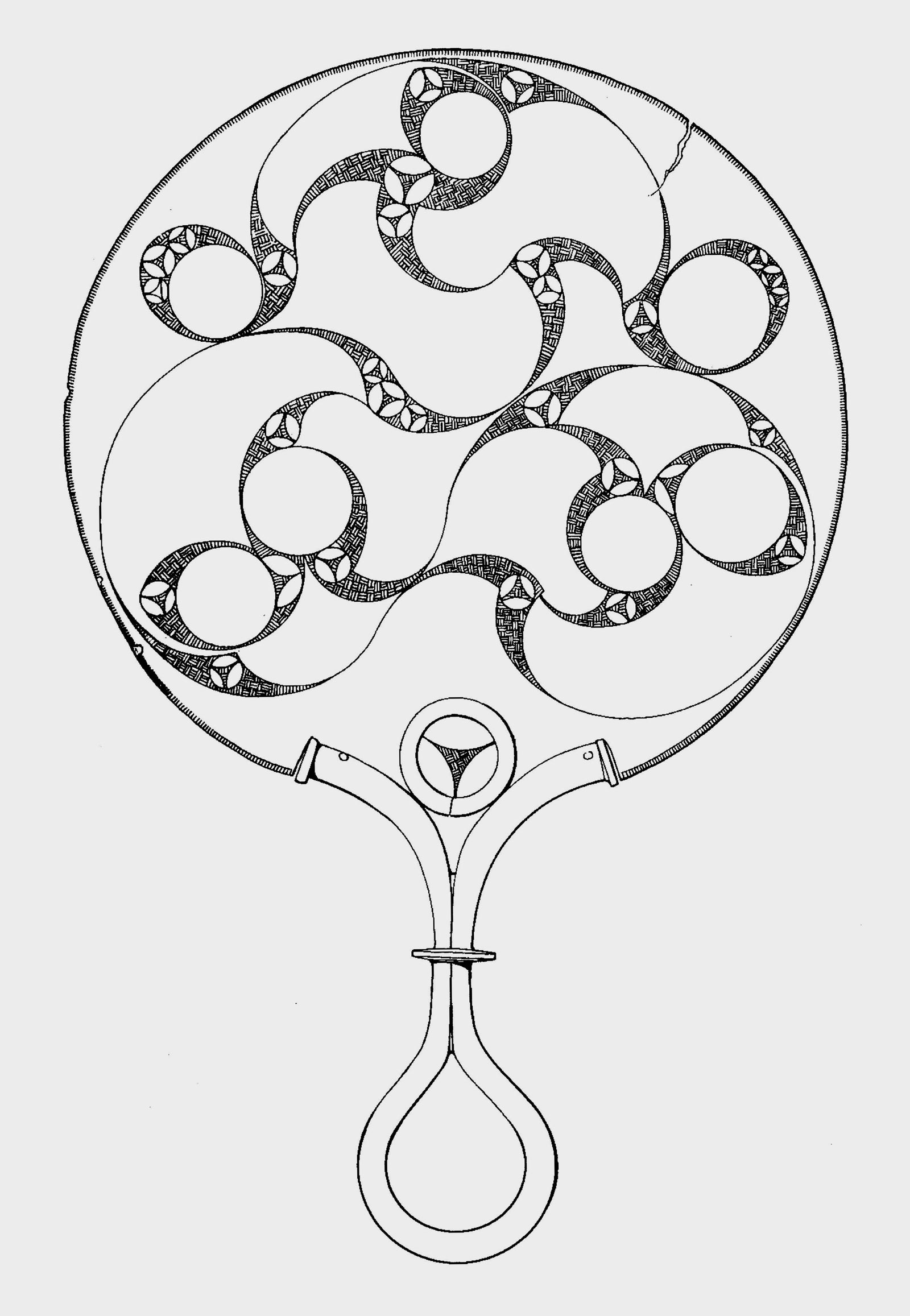

Fig 12. Pegsdon decorated mirror back drawing by Garth Denning, N Herts Archaeological Society.

Fig 13. Pegsdon copper-alloy mirror burial group, incl. silver brooch & potsherds.

Image © The Trustees of the British Museum.

“The mirror itself was intact but with the detectorists eagerness to get it out of the ground they were a little bit rough with it, so it had split in a couple of places. When it was conserved that was all repaired but surprisingly the handle was still attached, usually you find these things are separated buy the plough so it’s quite rare to find something like this in one piece. So it was in pretty good nik really, and the decoration had been very well preserved, it would have been polished on one side with the decoration on the back”.

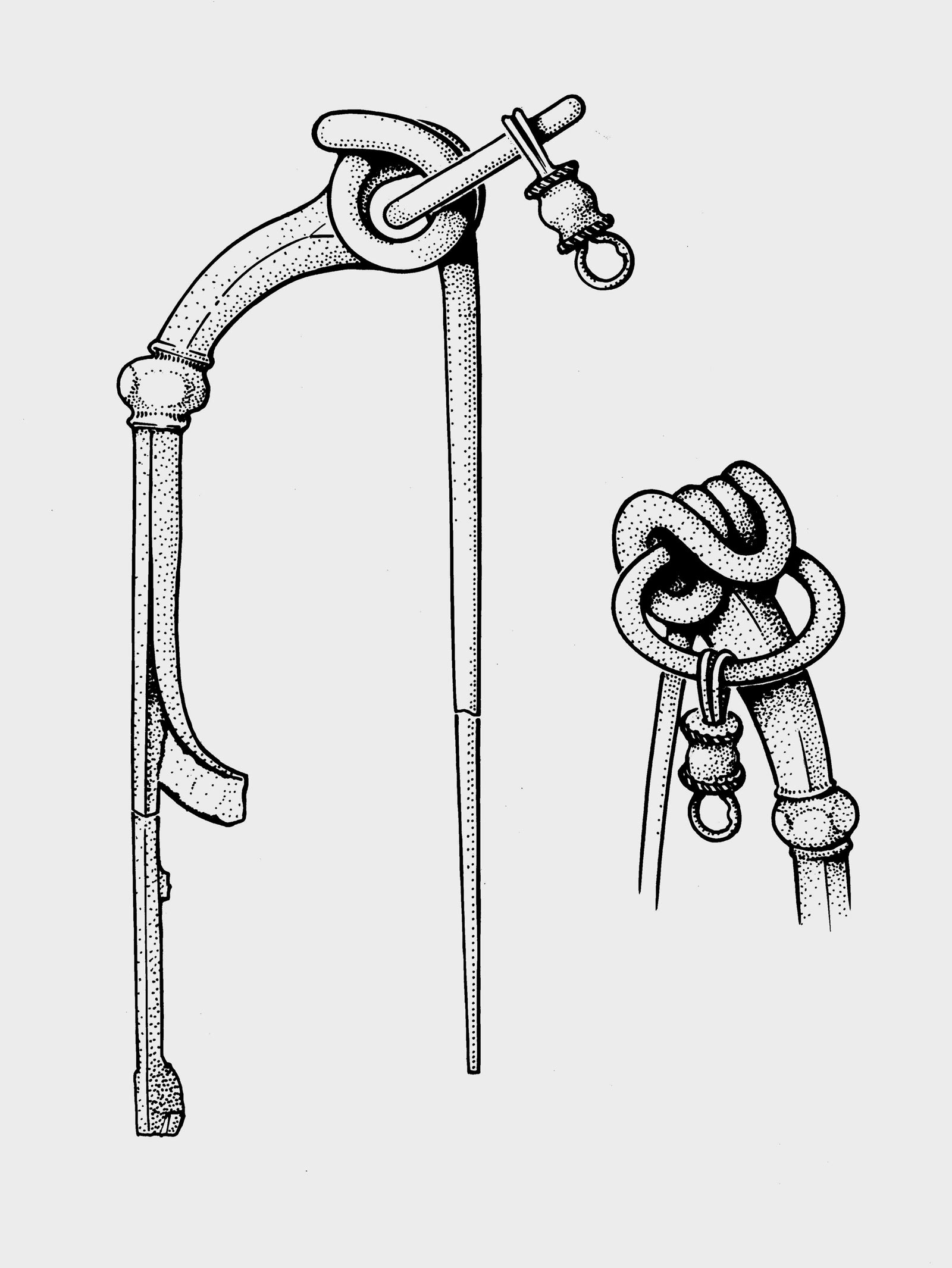

“The silver brooch (Fig. 15) found with it would have been part of a pair that were connected by a chain, but as is often the case you get one of the pair and you don’t ever find the other one. But I think in this case where we found a brooch which was quite quite obviously of a pair, the reason we don’t find the other one is because it wasn’t put in the ground in the first place. It may have been deliberately separated so that the mourners kept it as keep sake as way of a connection to the burial. The detectorists did search far and wide for the brooch’s twin and the chain but they never found anything, which is why I came to the conclusion that it was never in the ground in the first place”.

“As an archaeologist you know that these things are being brought to your attention because over the years you’ve built up a relationship with the hobbyists out there detecting, and then they trust you, and you in turn trust them, sometimes ending up with spectacular results. It’s all about relationships and trust”.

Fig 14. Plan of 2001 excavation of Pegsdon Iron Age mirror burial pit. Drawn by Gilbert Burleigh, North Herts Archaeological Society.

Fig 15. Iron Age silver brooch from Pegsdon mirror burial. Drawn by Garth Denning, N Herts Archaeological Society.

dea senuna the unknown deity

Dea Senuna: Treasure, Cult and Ritual at Ashwell, Hertfordshire, with Ralph Jackson and other contributors, March 19, 2018, The British Museum

Abstract: The Ashwell Hoard is an unprecedented find both in Britain and in the wider Roman world. In Britain there has been no equivalent discovery of ‘temple treasure’ within living memory. It is paralleled only by the 18th-century finds from Barkway, Hertfordshire (1743) and Stony Stratford, Buckinghamshire (1789). In contrast to the Ashwell Hoard those two finds preserve almost no information concerning their discovery or archaeological context. In terms of its finding circumstances, then, the Ashwell Hoard is exceptional even amongst the small number of precious metal votive hoards from Roman Britain. But it is exceptional in other ways, too, most notably in the inclusion of a silver figurine, unique gold jewellery and votive plaques of gold and by the proportionately large number of plaques with votive inscriptions and with die-stamped figural decoration. The silver figurine of Senuna, a hitherto unknown native British goddess, is unparalleled in Roman Britain. If the dedication of a large, high-quality, silver-gilt figurine is evidence of a votary of some means amongst the followers of Senuna so, too, and even more so, is the gold jewellery, which may be interpreted as a suite. It is a very rare survival outside Rome itself. Numerically, the greater part of the Ashwell Hoard is the collection of 20 gold and silver votive leaf plaques, which, in form and number, are a unique survival. The importance of the hoard, whose ‘new’ goddess caught the imagination of the public as well as the academic world, was such that it demanded an archaeological investigation of the find-spot. Its discovery triggered the fieldwork that illuminated the immediate setting of the hoard and then expanded that setting into the wider landscape. The progressive results of fieldwalking, geophysical surveys and excavations led to a fuller understanding of the circumstances surrounding the choice of site for the burial of the hoard, of the nature and use of the site itself and of its relationship to surrounding structures, settlements and natural landscape features. Almost the first find from the excavations was the missing silver pedestal from the silver-gilt figurine, a key find, and, better still, inscribed. In reconnecting the image of the female deity to the dedicatory vow, inscribed for the votary Flavia Cunoris, it instantly multiplied the meanings and hugely enhanced the significance of an already important object. That discovery set the tone for the excavations, which went on to reveal not a formal temple building, as initially suspected, but a unique and fascinating open-air ritual site, where feasting, religious activity and ritual deposition took place over a long period of time, seemingly extending as far back as the Bronze Age.

So the Ashwell Hoard (Fig. 16 – click to view the link) is the big one in the context of archaeological significance, it was the discovery of a deity that had never been heard of or recorded before. I could see by the beam on Gils face and the enthusiasm in which he spoke about this discovery that it was the biggest highlight of his long career. And again it’s something that Gil freely admits would not have been possible if it weren’t for the detecorists who were out searching the fields that day. The good relationships that Gil had built with local detectorists over the years certainly paid dividends for the archaeological world with this incredibly significant find. With a glint in his eye Gil recounted the following about this wonderful treasure.

“I went out to the site on the day the detectorists phoned me, I got there about an hour after the phone call was made, and everything was out on the side of the hole the detectorists had dug (Figs. 17, 18 & 19). It was a bright sunny morning and I could see straight away that not only were there images on these gold and silver plaques but some of them had inscriptions. I didn’t try to read and decipher them myself as they were still covered in dirt. It was about a week later when Ralph Jackson at the British Museum phoned me, he said, “It looks like we’ve got a new goddess called Dea Senuna that’s not ever been recorded before”. It still amazes me that in this day and age you can come across a new Romano/Celtic goddess that’s unrecorded, and that’s absolutely phenomenal.”

Fig 17. Scene at my arrival on Sunday morning 29/09/2002.

Fig 18. The unearthed hoard on the finder’s pullover 29/09/2002.

Fig 19. Searching for more of the treasure Sunday morning 29/09/2002.

“If I remember rightly the figurine (Fig. 20) had been placed on top of the gold jewellery and silver arms from the figurine, beneath which were the closely stacked gold plaques and then the silver-alloy plaques, but the pedestal base for the figurine was not in that pit. At the start of our excavations it was found about 5 metres away and it appears to have been deliberately buried separately. You can never really understand why people do these things, but they did, and that’s how we found it. It was definitely the base for the figurine which the conservators were able to prove without doubt because the figurines feet matched with the outline of the solder on the base. Why they would bury these things separately is anyone’s guess, but it may have been that one person had buried the bulk of the hoard and a relative was burying just the pedestal base as their separate and personal act of ritual.”

Gil carried on to say…

“Again on the Ashwell dig, and this was also deliberate I’m sure, we found part of a copper alloy plaque depicting a bull placed on a surface on one part of the site right in the centre of the ritual enclosure. We found the other half of the plaque deliberately placed in a little pit a few meters away. They were very clearly broken, separated and then buried separately for whatever motive, who knows. It could be two different devotees making an offering of one thing but they each wanted to make a separate offering so they broke it in two.”

Fig 20. The silver figurine of Senuna shortly after discovery 01/10/2002. Photo by Garth Denning.

Fig 21. Roman gold clasp brooch with carnelian intaglio depicting a lion on the day of discovery 29/09/2002. Photo by David Hillelson, The Heritage Network.

Fig 22. Conserved Roman gold neck ornament. Photo by Deb Hudson.

Fig 23. Conserved Roman gold votive plaque with image of Minerva

and inscribed dedication to Senuna. Photo by Deb Hudson.

Fig 24. Roman gem-set gold disc brooch unconserved. Photo by Deb Hudson.

Fig 25. Roman gem-set gold disc brooch conserved. Photo by Deb Hudson.

It was great to hear Gil’s recollections of these amazing discoveries and even better to be able to share them, along with some of the photos from the sites’ archives as well as other photos which Gil has provided (with permission) for use in this article (Including Figs. 21-25). Gil was also involved with more extensive excavations that took place at Ashwell in the following years which produced further insight to add to the archaeological understanding of the area (Figs. 26 – 33).

Fig 26. Gil Burleigh in foreground with other excavators, Ashwell 18/09/2005.

They are excavating clay oven bases used for cooking joints of meat consumed at religious

feasts in honour of Dea Senuna and other deities. Photo by Deb Hudson.

Fig 27. Looking east at part of 332 gravel surface on the west side of the 2004 excavation area. Photo by Gilbert Burleigh.

Fig 28. Looking south across the 2006 Ashwell excavation area.

Photo North Herts Archaeological Society.

Fig 29. Roman copper-alloy bow brooch from the Ashwell dig, 19/09/2005. Photo by Deb Hudson.

Fig 30. Pig deposit 311, Group C, view from south-west. Photo by Gilbert Burleigh 2004.

Fig 31. Some finds in deposit 522 on the central open-air platform, 2006. Photo by Gilbert Burleigh.

Fig 32. Fragment of a Roman decorated silver-alloy votive plaque, similar to those in the Senuna hoard, from the 2005 archaeological excavation. Photo by Deb Hudson.

Fig 33. Visitors to the Ashwell dig. 18/09/2005. Photo by Deb Hudson.

passing the batton

Shortly after making contact with Gil I happened to mention it to Keith at North Herts Museums. Keith revealed that Gil has been a direct influence on many aspects of his own archaeological working life. I feel sure that Gil’s views on detectorists has played its part in shaping Keith’s own stance on our endeavours, and this feels quite evident because of the trusted relationship that I now share with him. Given Keith’s enthusiasm and willingness to add invaluable insights and contributions to some of my previous articles, it seemed only fitting to ask him to share a little of his experiences and memories about Gil.

“I was born and grew up in Letchworth Garden City, and was familiar with the former Letchworth Museum, which I often visited. This became especially frequent after I started at the Grammar School, on the opposite side of the Town Square. During 1974, I skipped revision for my O-Levels to help out on the excavation at Wilbury Hill, run by the then curator, John Moss-Eccardt, and the North Herts Archaeological Society. I joined the Society, and later that year, met Gil, who had been appointed Keeper of Field Archaeology for the Museums Service. Gil was someone I looked up to enormously, as he had a job that I wanted when I was older.”

“I remained a member of the Archaeological Society until going to University in 1977, studying Archaeology (of course!). On graduating in 1980, I made the decision to stay in northwest England, although I was unable to get any work in my hoped-for profession. After drifting through a succession of short-term jobs, I ended up as a nightclub DJ in Manchester, something I had never expected. Following a row with my boss (who I discovered had been cheating on his girlfriend in my flat) I returned to the south in late 1985. One of the first jobs I saw advertised in Hitchin Job Centre was for excavators in Baldock. Naturally, I applied and started work (now 38 years ago) with Gil as my boss.”

“Gil has a knack for recognising things that many other archaeologists would just ignore. This included a significant sequence of fifth- and sixth-century ‘post-Roman’ deposits in Baldock, something that remains exceedingly rare on this type of site. He has high standards for excavation (vertical sections, ultra-clean trowelled surfaces and so on) that I have carried with me since then. His keenness to work with metal detectorists was apparent from the moment I joined the team: they would scour the spoilheaps and surrounding farmland for artefacts that would add to the picture gained from digging with trowels and mattocks. When I eventually moved on in 1990, I took his ideas with me and tried to apply them in Chester. In one of the great ironies I could never have foreseen, I returned to North Herts in 2004 to take up what had effectively been Gil’s old job!”

Some Sunday afternoon reading for me and the pooch with the

British Museum Research Publication that Gil co-wrote. You can purchase a copy

of Research Publication 194 on the link at the end of this article.

the way forward

After meeting Gil and having the chance to talk about these amazing discoveries, it’s left me with no doubt about the importance that us detectorists play in stitching together the archaeological tapestry that is our history. It seems to me that Gil was ahead of his time with his views on the detecting community and knowing the importance of tapping into that resource, and make no mistake, the metal detecting community is a valuable resource. By building the trusted relationships that he did, the discoveries highlighted here have been properly recorded, researched and preserved for future generations to marvel at. The Ashwell Hoard in particular is still on display at the British Museum and it’s well worth a visit, along with all the other amazing exhibits they have on display. Further information about the Ashwell Hoard can be found on the Ashwell Museum website by clicking the link at the end of this article.

A selfie taken of Gil and myself at Dane Field as he was explaining the lie of the land.

My meetings with Gil revealed that not all archaeologist’s were against the metal detecting community during the 1970’s/80’s when the STOP (Stop Taking Our Past) campaign was in full swing, which for me was a real eye-opening surprise. Suffice to say things have come a long way since Gil started recording detectorists finds back in 1976 and even more so since the introduction of the Portable Antiquities Scheme in 1997, and in my experience general relations between detectorists and archaeologists has much improved too. Thats not to say that there aren’t still mishaps and mistakes made on both sides of the fence, but the realisation that detectorists and archaeologists do well to work together will ultimately pay dividends for our historical heritage. Working together to protect that heritage is definitely the way forward. Finally, I will end this article with a hope that maybe one day I will turn up at Keith’s door with a briefcase full of gold Roman coins, after all, it’s not like it hasn’t happened before!